To coincide with our new collection, we’re celebrating history’s Emotional Utilitarians. Designer-makers who committed themselves to the very plainly functional, with a touch of romanticism. Eileen Gray, pioneer and lover of lacquer, gives her middle name and particular brand of modernism to Moray.

In 1927, Eileen Gray designed the E-1027 table. A circular rim with a celluloid top, poised on an adjustable arm of tubular stainless steel and balanced on a semicircular base, which has since become an icon of modernist design. She carefully considered its lightweight structure, height, and proportions, all so her guests could enjoy their toast in bed without spilling crumbs.

The table was one of over 200 bespoke fittings designed for her house of the same name on the French Riviera, her first, untrained – triumphant – venture into architecture. While enforcing the same straight lined ideals of her Corbusian modernist peers, Gray was clear in separating herself from the boys’ club that they represented, through a greater respect for the human side of architecture: ‘The poverty of modern architecture stems from the atrophy of sensuality. The dominance of reason, order and maths leave a house cold and inhumane.’

The table was one of over 200 bespoke fittings designed for her house of the same name on the French Riviera, her first, untrained – triumphant – venture into architecture. While enforcing the same straight lined ideals of her Corbusian modernist peers, Gray was clear in separating herself from the boys’ club that they represented, through a greater respect for the human side of architecture: ‘The poverty of modern architecture stems from the atrophy of sensuality. The dominance of reason, order and maths leave a house cold and inhumane.’

‘Sometimes all that is required is the choice of a beautiful material worked with sincere simplicity.’

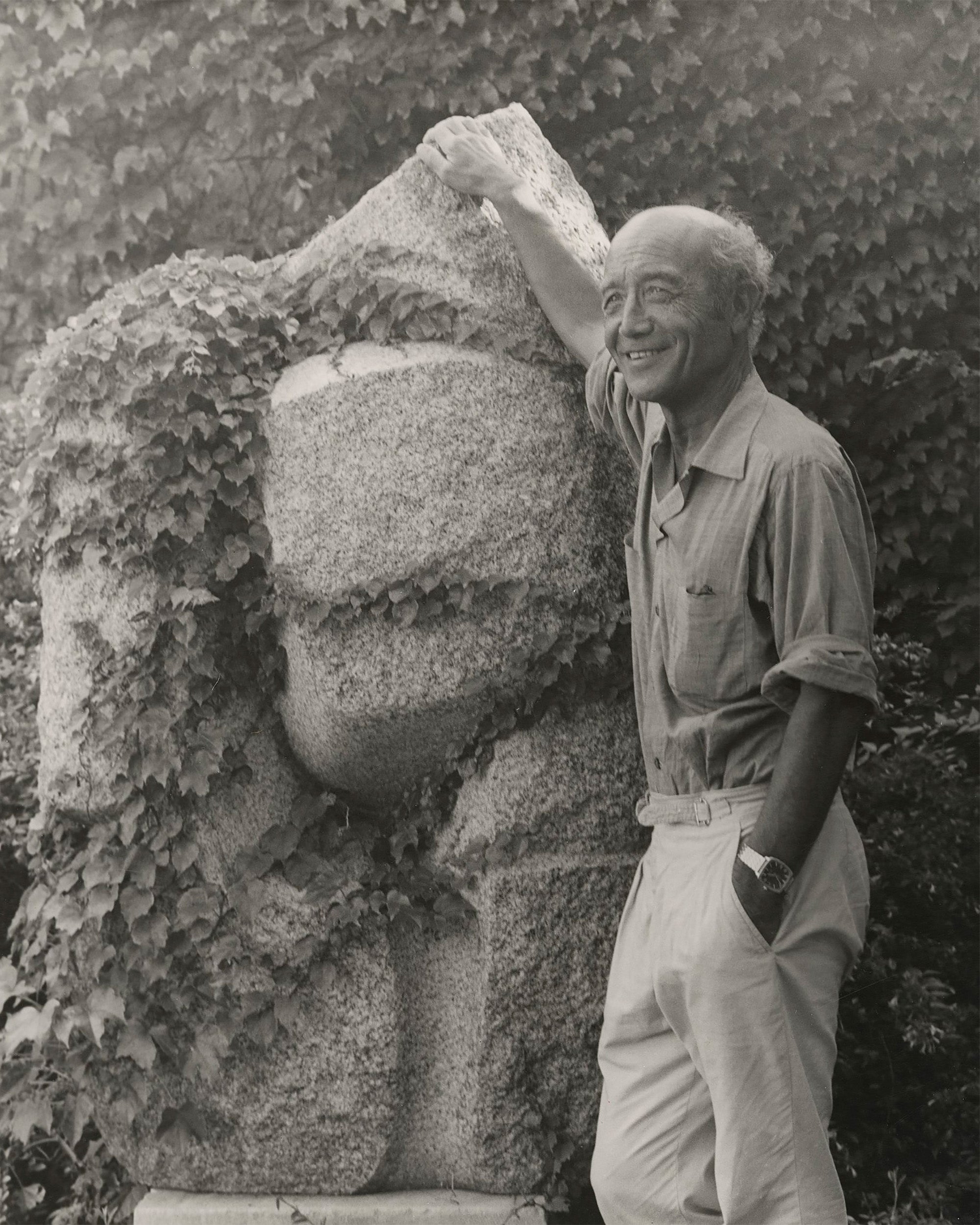

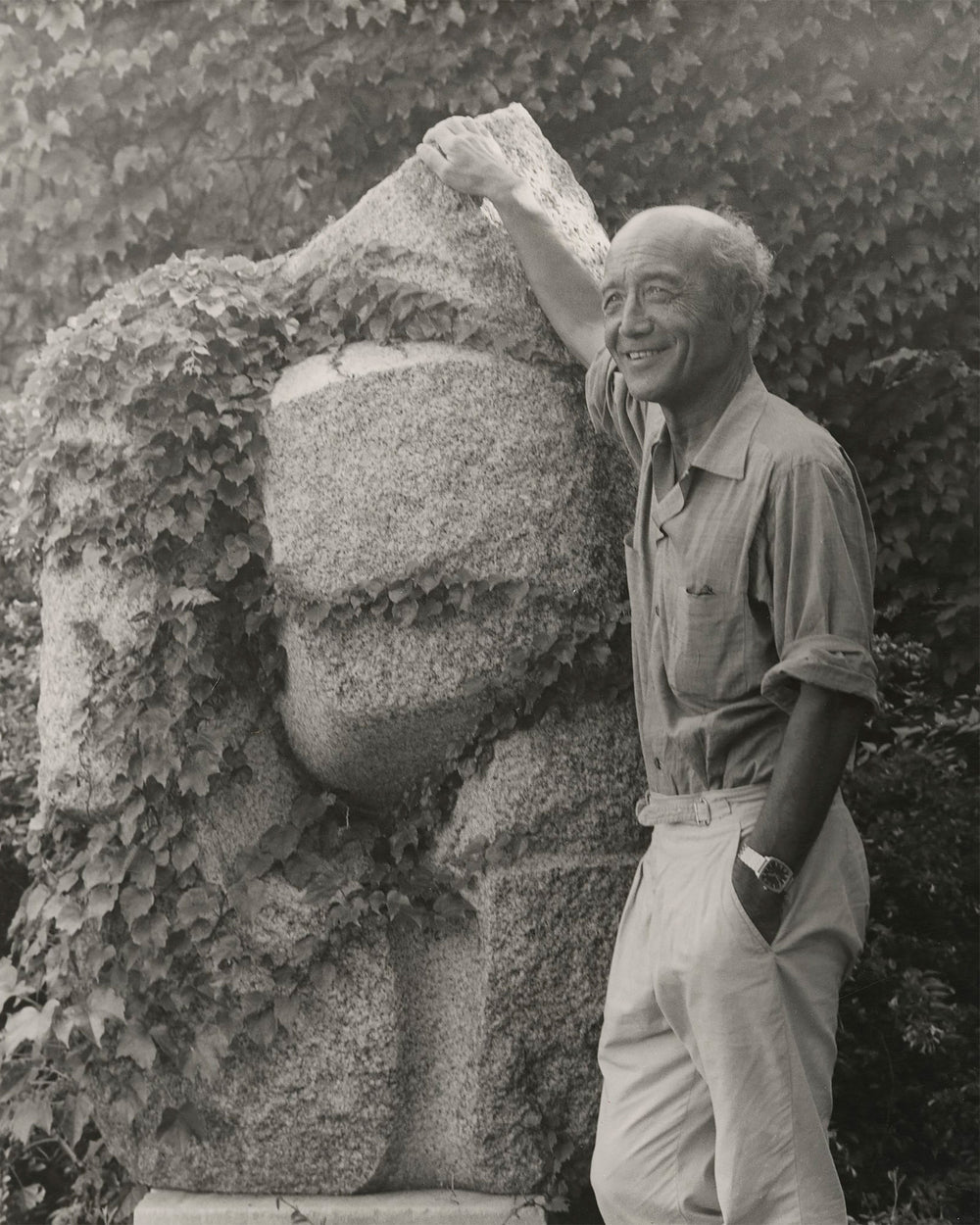

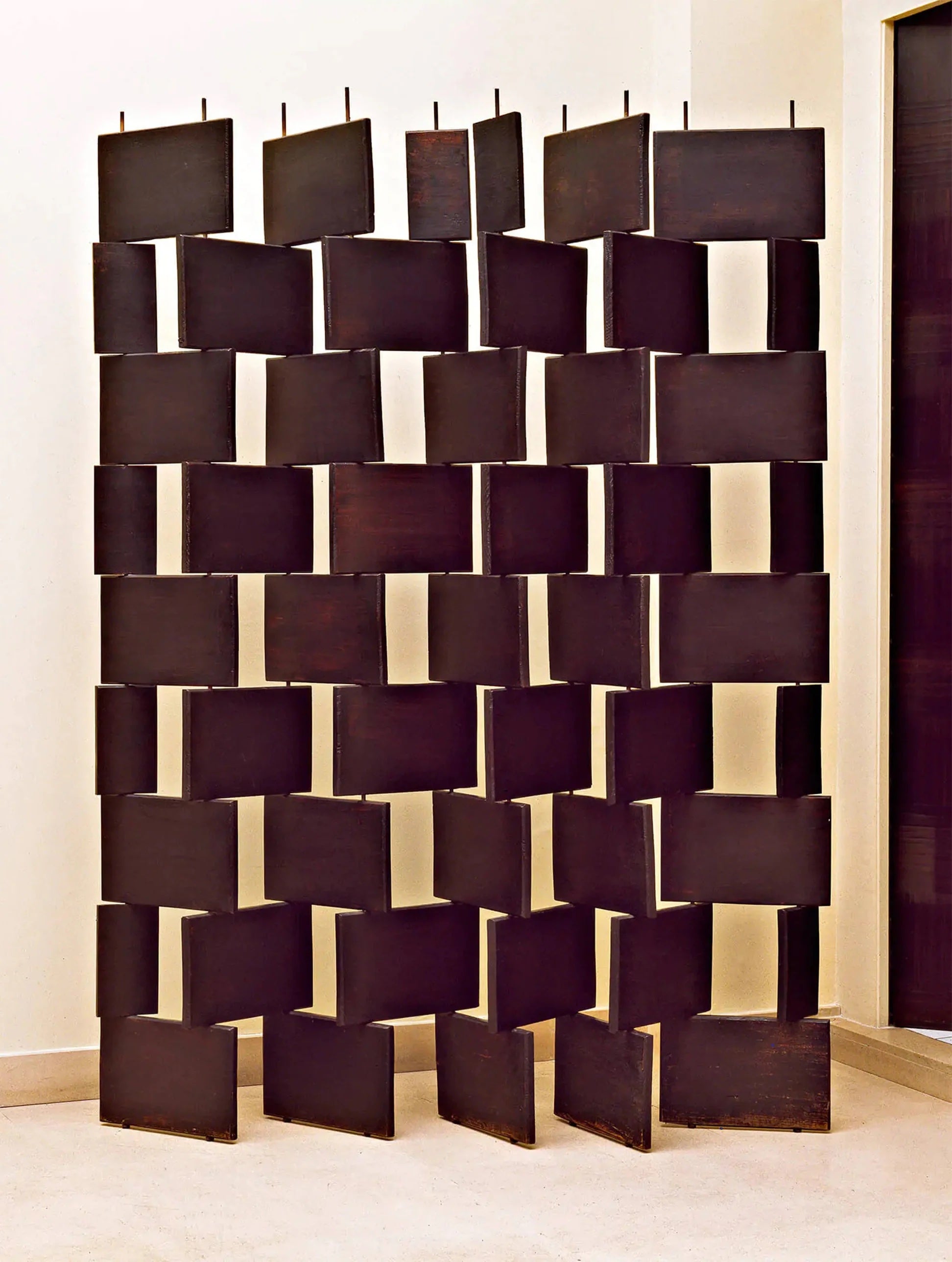

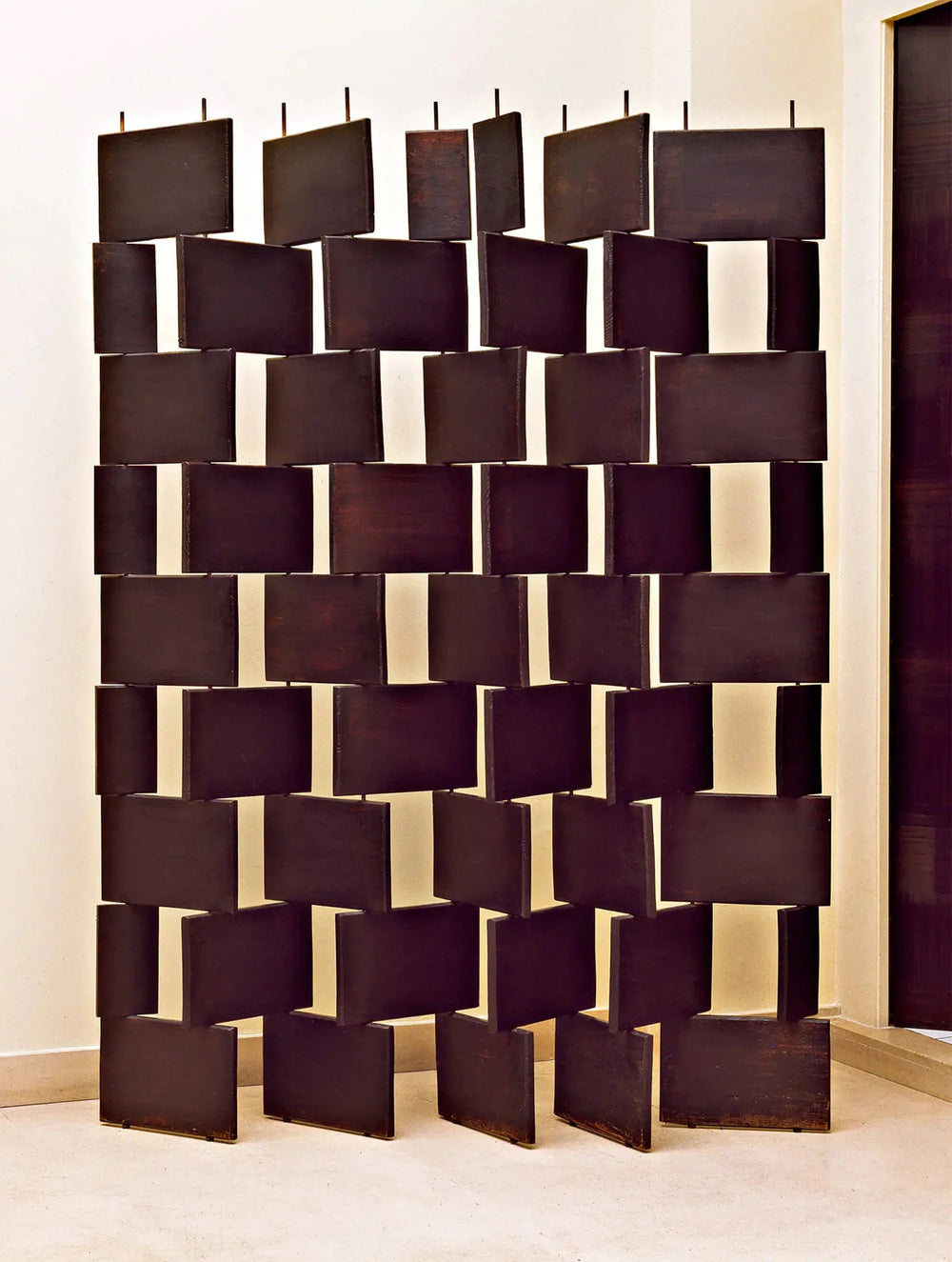

This duality of ‘form follows function’ and beauty had been a constant motif throughout her career. In the 1920s, she dedicated herself to making something ‘useful’, with a series of ingenious articulated room-divider screens. The above example is formed of fifty rectangles, arranged into four rows horizontally and seven vertically, each composed of three horizontal rectangles, and one, smaller vertical, on interchanging ends. The result is a simple, geometrical form, which tessellates as the screen is moved, a strict modernist geometric rebuttal to the prevailing ornament of Art Deco.

And yet it is all contained within a materially sensuous setting. While her modernist peers were rejecting traditional craftsmanship, Eileen embraced the ancient art of Asian lacquer to bring her design to life. She apprenticed herself to Seizo Sugawara, a Japanese master artisan and fellow foreigner in Paris, and learned his trade for several years before ever exhibiting her work in the medium.

The practice involves meticulously painting a surface with lacquer in a warm, dust-free place, monitoring for a day as it drys, and polishing, before repeating the process over at least a dozen layers. This form of meditative constructive practice was at that time foreign to the practically focussed realms of modernist design.

Ancient practitioners of lacquer would work by the sea for the required humidity. Eileen found a modern compromise. She worked in her bathroom.

And yet it is all contained within a materially sensuous setting. While her modernist peers were rejecting traditional craftsmanship, Eileen embraced the ancient art of Asian lacquer to bring her design to life. She apprenticed herself to Seizo Sugawara, a Japanese master artisan and fellow foreigner in Paris, and learned his trade for several years before ever exhibiting her work in the medium.

The practice involves meticulously painting a surface with lacquer in a warm, dust-free place, monitoring for a day as it drys, and polishing, before repeating the process over at least a dozen layers. This form of meditative constructive practice was at that time foreign to the practically focussed realms of modernist design.

Ancient practitioners of lacquer would work by the sea for the required humidity. Eileen found a modern compromise. She worked in her bathroom.

Moray

Antidote to ornament.

Drawing on Eileen’s lacquered pieces, we’ve created our own screen. A screen for the human head. Gray, a simple yet sensuous cat-eye composite of a tripartite acetate structure. Monochrome Black, Bone, and Russet acetates interlock to recall the juxtaposed elements of her screens.

Its undulating and contrasting colour also takes inspiration from Gray’s experimental S-Chair, differentiating the different functional parts of the frame – nose bridge, brow, temple tips. Like the many stages involved in the ancient art of lacquer, Moray was created using four separate stages of cutting and lamination, creating a many-layered final frame.

Edit: Moray is now sold out. You can request to remake the frame through our Bespoke service.

Edit: Moray is now sold out. You can request to remake the frame through our Bespoke service.