Spectacles are not new to surrealism. Marcel Mariën’s The Untraceable is a pair of spectacles with a single lens (should that be: a spectacle?). It’s the archetypal surrealist object - one that refuses to comply with our attempts to use it. The same can be found in other canonical surrealist objects, like Man Ray’s Gift, an iron whose very ability to glide is obfuscated by the spiky tacks that are attached to its surface, or Meret Oppenheim’s Object, a teacup, saucer and spoon set bristling with animal fur.

This stems from the 1930s, when André Breton’s surrealist group became particularly obsessed with subverting everyday objects. Breton himself called for a ‘total revolution of the object’, a changing of the way we look at the things around us, a destabilisation of our privileged position of superiority over the inanimate. The surrealists proceeded to challenge the human-object relationship.

Inspired by the Design Museum’s exhibition, Objects of Desire , we set about creating a series of spectacle experiments as a modern response to surrealism’s object obsession.

This stems from the 1930s, when André Breton’s surrealist group became particularly obsessed with subverting everyday objects. Breton himself called for a ‘total revolution of the object’, a changing of the way we look at the things around us, a destabilisation of our privileged position of superiority over the inanimate. The surrealists proceeded to challenge the human-object relationship.

Inspired by the Design Museum’s exhibition, Objects of Desire , we set about creating a series of spectacle experiments as a modern response to surrealism’s object obsession.

Turning the inside out.

Surrealism at its very core consists of turning the inside out. Depictions of the human body gives us much of the movement's most shocking and disruptive imagery, often problematising the delineation between inanimate object and body, or exposing the insides.

During the 1930s, Meret Oppenheim produced a variety of such objects, including designs for a pair of gloves that externalise the inner vein system of the hand, problematising the inner/outer relationship between glove and hand. The gloves, realised in collaboration with Elsa Schiaparelli in the 1980s, are a contradiction in form. A wearable embodiment of the hands’ inner workings.

During the 1930s, Meret Oppenheim produced a variety of such objects, including designs for a pair of gloves that externalise the inner vein system of the hand, problematising the inner/outer relationship between glove and hand. The gloves, realised in collaboration with Elsa Schiaparelli in the 1980s, are a contradiction in form. A wearable embodiment of the hands’ inner workings.

We applied the same reasoning to a pair of spectacles, with finely detailed blood red temples that bring the curving progress of the optic nerve to the outside of the head. The lens is replaced with a laminated acetate eyeball discs. The pupil hole in the centre is just big enough to see through, but restricts vision, refuting the function of the pair of spectacles.

Broken dreams.

Surrealism so often confronts our desire for perfect wholeness with images of destruction and fragmentation. Dalí’s paintings, with their melting objects or exploded views, have become some of the most popular examples of surrealist iconography. These destructive images are part and parcel of the surrealism’s ambition to rupture the bounds of rational thought.

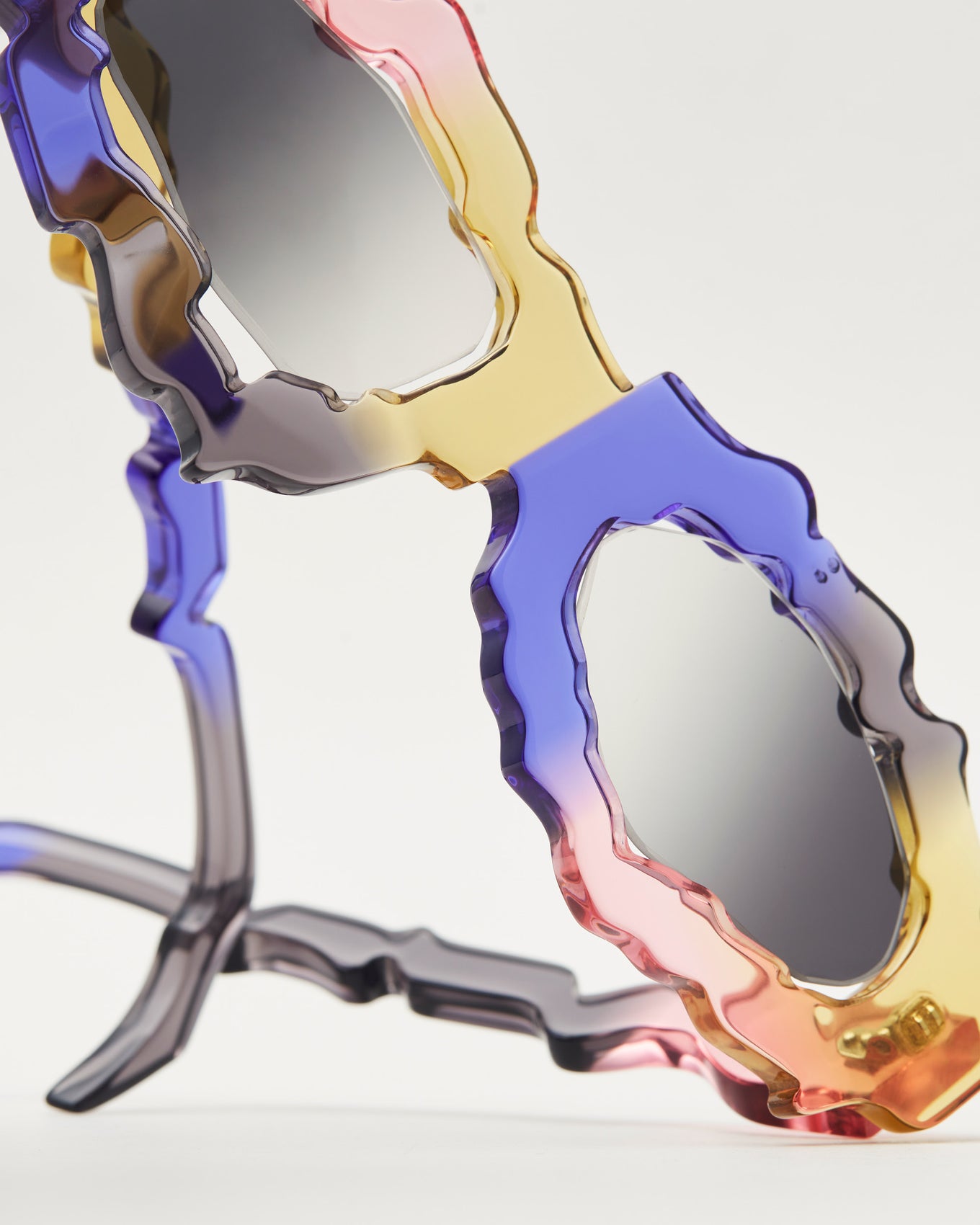

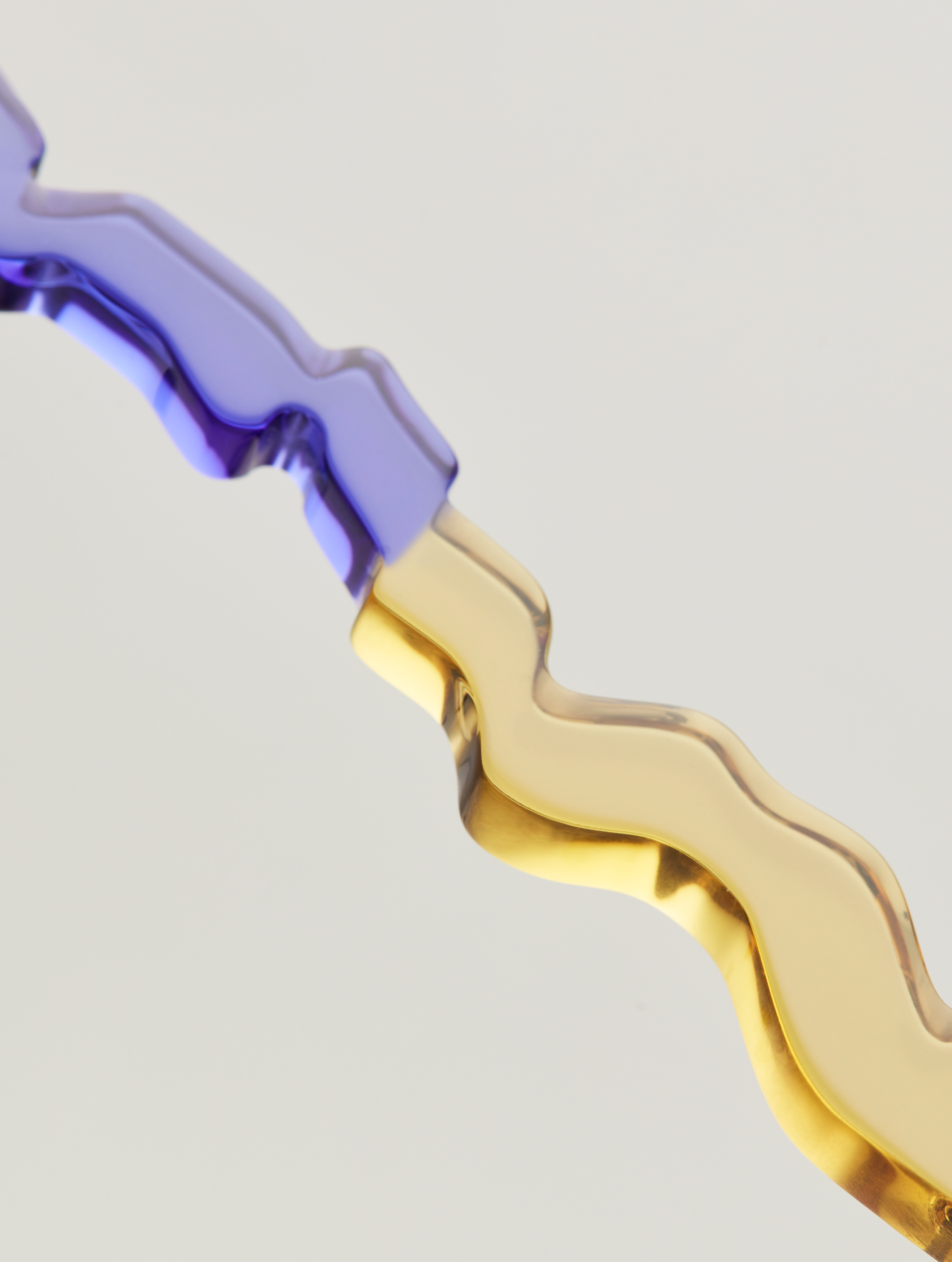

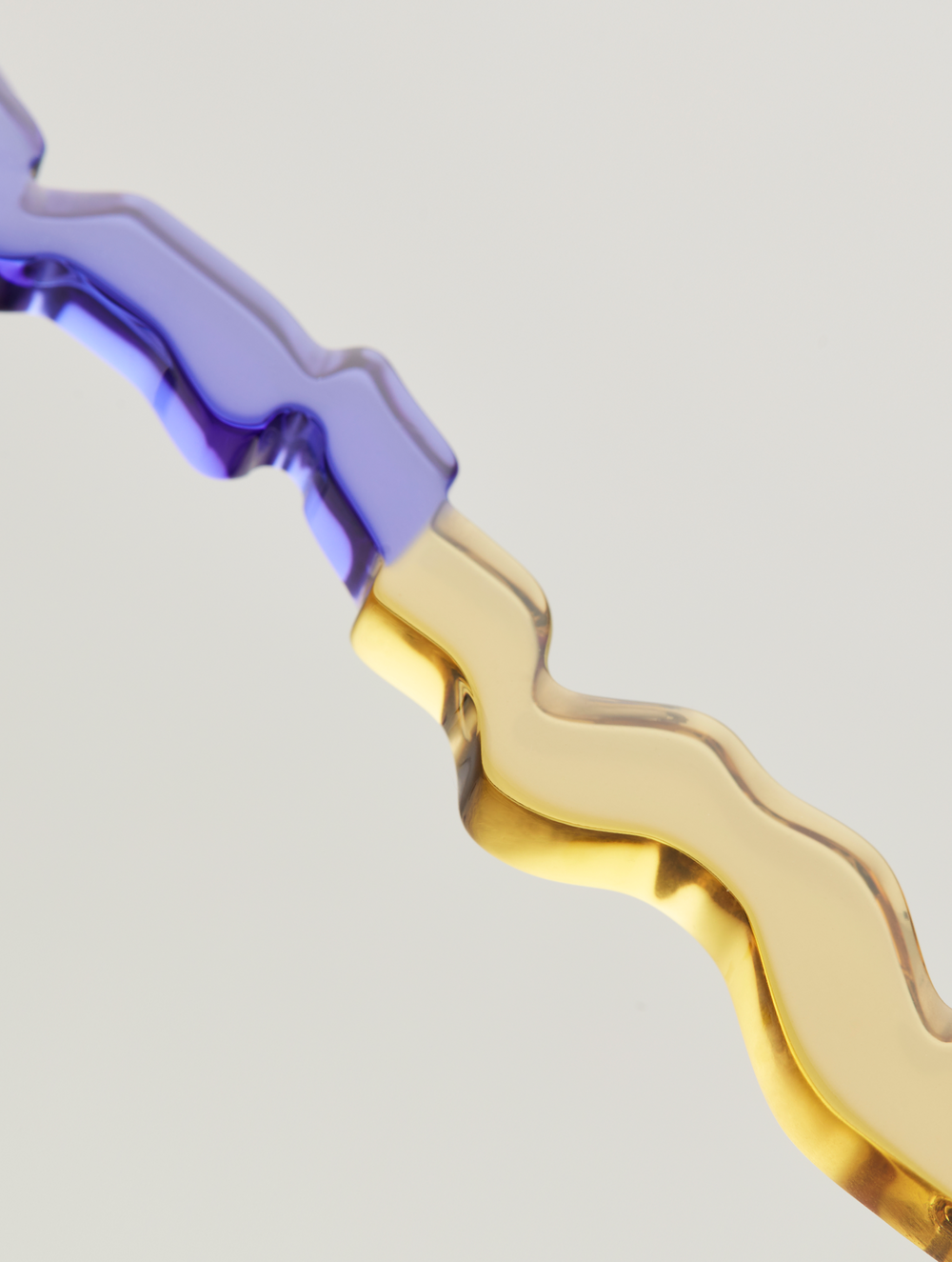

Our final frame extrapolates from this destructive urge, in conjunction with kaleidoscopic colours that nod to the surrealist fascination with the dream. Shattered and jagged combinations of acetate melded together, with a lens that seems to be melting out of place. At once broken and whole.

Chance encounters.

‘As beautiful as the chance encounter on a dissection table between a sewing machine and an umbrella.’ This quote from 19th century poet the Comte de Lautréamont was favoured by the surrealists as a description of the poetry derived from the juxtaposition of two things seemingly at odds with each other. As such, surrealist objects often employ materials paradoxically at odds with their function, constituting a collision of two competing realities.

Take Wolfgang Paalen’s Articulated Cloud of 1938, an umbrella made of sea sponge. The recognisable form of the umbrella (with a knowing nod to the aforementioned Lautréamont quote) is disrupted by its strange and anti-functional rendering in sponge. It’s an unsettling encounter between hardness and softness, the manufactured and the natural, functionality and uselessness. Through a bringing together of textural and theoretical opposites, Paalen succeeds in Breton’s ambitions for the surrealist object: ‘To aid the systematic derangement of all the senses… it is my opinion that we must not hesitate to bewilder sensation.’

Take Wolfgang Paalen’s Articulated Cloud of 1938, an umbrella made of sea sponge. The recognisable form of the umbrella (with a knowing nod to the aforementioned Lautréamont quote) is disrupted by its strange and anti-functional rendering in sponge. It’s an unsettling encounter between hardness and softness, the manufactured and the natural, functionality and uselessness. Through a bringing together of textural and theoretical opposites, Paalen succeeds in Breton’s ambitions for the surrealist object: ‘To aid the systematic derangement of all the senses… it is my opinion that we must not hesitate to bewilder sensation.’

Our own attempts to bewilder sensation are simplified. We melded the spectacle form with that of a puffer jacket, cut up and reattached to its heavy set body so that its plush form bulges over the edges, a conjunction of hard and soft.